Event structure: Difference between revisions

→Setting up events: Add contents |

→Subdiagram Labels: Remove section (see Subdiagram) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

<br clear="all"> | <br clear="all"> | ||

== Timeout behavior == | == Timeout behavior == | ||

<br clear="all"> | <br clear="all"> | ||

Revision as of 19:27, 26 July 2019

|

This page is under construction. This page or section is currently in the middle of an expansion or major revamping. However, you are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. Please view the edit history should you wish to contact the person who placed this template. If this article has not been edited in several days please remove this template. Please don't delete this page unless the page hasn't been edited in several days. While actively editing, consider adding {{inuse}} to reduce edit conflicts. |

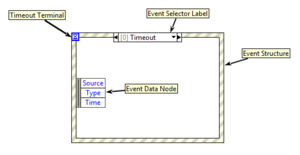

An Event Structure is a primitive structure that can have multiple subdiagrams (also known as "Events"), one of which is selectively executed at runtime. The structure waits for an event to occur, or until the timeout elapsed. While it waits, it doesn't take up any CPU time. Events can be triggered by user input or programmatically by the software. If an event happens while another event is executing, the new event is put on the event queue.

The event queue

Setting up events

Events can be setup via the right-click menu options:

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

| Edit Events Handled by This Case... | Opens the configuration dialog for the current event case. |

| Add Event Case... | Adds a new event case to the structure and opens the configuration dialog. |

| Duplicate Event Case... | Makes a copy of the currently selected event in a new event case and opens the configuration dialog. |

| Delete This Event Case | Deletes the currently selected event case. |

User events (dynamic events)

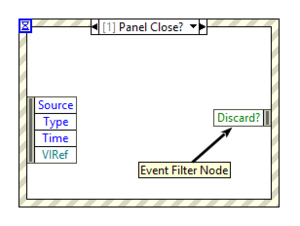

Filter events

Timeout behavior

Edit Events

Event sources

Application

This VI

Dynamic

Panes

Splitters

Controls

Lock panel (defer processing of user actions) until the event case completes

Limit maximum instances of this event in event queue

History

Best practice

- Use the Producer/Consumer design pattern to execute time-consuming tasks outside event structures. This will keep the user interface responsive.

- Use Set Busy and Unset Busy when executing long-running events to give the user a visual feedback.

- Use only one event structure in a while loop.

- Never handle the same event in multiple event structures.

- Never place an event structure within another event structure.

See also

- Event Inspector Window

- Functions Palette/Programming/Dialog & User Interface/Events

- Producer/Consumer

External links

- National Instruments: Event-Driven Programming in LabVIEW

- National Instruments: Caveats and Recommendations when Using Events in LabVIEW

| |

This article may require cleanup to meet LabVIEW Wiki's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. |

Behaviour

LV BE (Before Events) had the panel and diagram behaving as asynchronously as possible WRT one another. A control periodically handled UI events from the user and dropped the value into its terminal. Independently, the diagram takes the current value when it is needed and does its work. There is no synchronization between when the UI event is handled, when the value in the terminal changes, and when the diagram reads it. It is often a very simple way of writing your code and mimics how most hardware works. So why do events?

The primary reason for the events feature is to allow synchronization between the UI and the diagram. First off, the diagram gets notification of a value change. It is guaranteed not to miss user changes or to burn up the CPU looking for them. In addition to the notification, the diagram gets a chance to respond, to affect the rest of the UI, before the rest of the user input is evaluated. Maybe this part needs an example.

Lets look at polled radio buttons. In theory, your diagram code polls fast enough to see each change in the radio buttons so that it can make sure that the previous button is set to FALSE. But when the user is faster than the diagram and presses multiple buttons, what order did they press them in? There has to be a fixup step to break the tie and pop out all but one button to FALSE regardless of the order the user clicked them.

With events, when the user clicks on a button, the panel is locked and will not process the next user click until the diagram finishes. This allows the diagram to see the button changes one at a time in the same order as the user presses.

Another example, perhaps a better one, is a panel with three action buttons: Save, Acquire, and Quit. The order that the presses are responded to is important, so the polling diagram has to "guess" whether to Save and then Acquire or Acquire, then Save. The Event Structure knows the order and the code in it is synchronized with the UI allowing for a better, more friendly UI.

Getting back on topic, the event structure introduces the synchronization, but the downside is that as with all synchronization, it allows for deadlocks when not used in the right way. As already discovered, nesting event structures is almost never the right thing to do, at least not yet.

As noted earlier, it is possible to leave the Event Structures nested, but turn off the UI locking. This appears to solve the problem, but it isn't how I would do it. I think a much better solution is to combine the diagrams of two structures into one. The value change for hidden controls will not happen, but it doesn't hurt to have it in the list of things to watch for. Another option is to place them in parallel loops. This will let the first structure finish and go back to sleep.

Why doesn't the event structure register local variable changes?

The main reason for not sending events for programmatic value changes is to avoid feedback.

A happens. In responding to A, you update B and C. If responding to B or C results in changing A, then you have feedback and your code will behave like a dog chasing its tail. Sometimes the feedback will die out because the value set will match what is already there, but often it will continue indefinitely in a new type of infinite loop.

One solution to this is to utilise User Events. Then you either have the value change and the set local both fire the user event, or you can combine the event diagram to handle both and just fire the event when writing to the locals. Today, you can accomplish this with the queued state machine using the state machine to do all the common work and just having the event structure pass things to the queue.

User Events

User Events are programmatically generated events. You define what data they carry and when they fire. They can be handled by the same event structure as the User Interface events. An advantage of User Events (unlike User Interface Events) is that LV doesn't need to perform a context switch into the UI thread. [1]

Locking The Panel

Given the synchronized mechanism of events, it is pretty easy to repost events to another queue or turn off locking and synchronization. If the event structure isn't synchronized, it would be impossible for the diagram to add it and become synchronized with the UI, so it is at least necessary for event diagrams to be able to lock the panel.

Should it be the default?

In our opinion, yes. When responding to an event, it is pretty common to enable/disable or show/hide some other part of the display. Until you finish doing this, it is wrong for LV to process user clicks on those controls, and LV doesn't know which controls you are changing until you are finished.

Additionally, it isn't the best idea, but what happens when the event handler does something expensive like write lots of stuff to a database inside the event structure? If the UI is locked, then the user's events don't do much, ideally the mouse is made to spin and this works the same as a C program. The user is waiting for the computer, and the UI more or less tells the user to be patient.

If the UI isn't locked, the user can change other things, but you can't execute another frame of your event structure until this one is finished. This is a node. It must finish and propagate data before it can run again, and the loop it is probably in can't go to the next iteration until it completes. You would have low level clicks being interpreted with the current state of the controls before the diagram has a chance to respond. This is sometimes the case, so it is possible to turn off event handling on the cases where you know that you may take awhile and you do not affect the state of the UI.

If you need to respond to the events in parallel, you can make a parallel loop, add an event handler for the other controls, and handle them there while this one churns away. That will work fine and it is IMO clear from the diagram what is synchronized and what is parallel. Taken to an extreme, each control has its own loop and this approach stinks, but it is a valid architecture. Note that for this to work well, you need to turn off the UI lock or have a node to release it.

Another way of doing expensive tasks is to have the Event Structure do the minimum amount necessary before unlocking -- treat them like interrupts. Have the event structure repost expensive operations to a parallel loop or fire up an asynchronous dynamic VI. Now your event structure is free to handle events, your UI is live, LV is still a nice parallel-friendly language, and your diagram just needs to keep track of what parallel tasks it has going on.

In the end, I'm not sure I can convince you, but if you continue to experiment with the different architectures that can be built using the Event Structure, I think you will come to agree that it normally doesn't matter whether it is locked or not. There are times where it is really nice that it is locked, and occasionally you may turn off locking so that the user can do additional UI things up to the point where synchronization is necessary again. For correctness, we decided that locking should be the default.